Get our Newsletter

-

- Reviews

- Narrators

-

Features

- Audiobook ClubStart a conversation with your book club

- Best Audiobooks2023 Best Audiobooks

- ArticlesDiscover the diverse voices of audiobooks

- NarratorsSpotlight on popular narrators

- AuthorsAuthors talking about their audiobooks

- Upcoming TitlesFind upcoming audiobook release announcements

- Kids and TeensListening selections for kids & teens with age levels

- Audie Awards 2024 Audie Awards

- Subscribe

- About

- Articles

Recent audiobooks

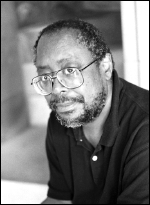

Talking with Edward P. Jones

“That 1901 winter, when the wife and her husband were still new to Washington, there came to the wife, like a scent carried on the wind, some word that wolves roamed the streets of the city after sundown . . . ” So begins Edward P. Jones’s new collection of short stories, ALL AUNT HAGAR’S CHILDREN. It is no mistake that that first line evokes the cadence of an oft-told fable. For, while the stories in Jones’s collection are specifically about black people moving from the rural South to Washington, D.C., they explore common and enduring themes of love and longing, kindness and loss, understanding and misunderstanding.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author (THE KNOWN WORLD) set most of the pieces in the 1950s and ’60s because, as he says, “I was coming into my own then, and the world seemed fresh and new.” Yet the stories also have an intentional timelessness. Jones adheres to the “hundred-year rule,” which dictates that if readers a century from now won’t understand a reference, a writer shouldn’t use it. Instead of mentioning television shows and name brands that will soon disappear from our collective consciousness, he washes himself in the archetypal concerns of a people trying to find their own right place and in the remembered speech of another time and location.

“You hear folks talking when you’re a child and you’re not supposed to listen, but you do. Most of the adults I knew growing up had been born and raised in the South. They brought that culture of storytelling with them. I absorbed things.” He pauses, then adds with a bemused smile, “Can’t really say what, but I know it’s there. You can’t help but be influenced.

“‘Every good-bye ain’t gone’ is one of my mother’s expressions that I used in a story. And when a character made promises to his wife’s parents, I had the wife say, ‘You just sat there sopping up my daddy’s gravy with my mama’s biscuits.’” As Jones recites, the words roll off his tongue with an unctuous emphasis that suggests admiration for the oral power of the written word.

Jones quite often reads aloud when he writes, as it helps him create believable dialogue and hear the rhythm of sentences. “The language of a book should be as beautiful and poetic as you can make it,” he says. “It should not lie flat on the page.”

While Jones listens to his own words as he works, he doesn’t listen often to audiobooks. But he has heard the beginning of Peter Francis James’s narration of ALL AUNT HAGAR’S CHILDREN and says, “It sounded wonderful--so wonderful that it made me want to hear the rest of it.” So, he may be an audiobook fan in the making.

Meanwhile, Edward Jones will continue simply to read aloud to himself as he examines our universal history. “We’re all creatures of everything that happens--all the past,” he says with the relish of a conjuror. “And that past is full of stories.”--Aurelia C. Scott

DEC 06/JAN 07

© AudioFile 2006, Portland, Maine

Photo © Jerry Bauer

The latest audiobook reviews, right in your inbox.

Get our FREE Newsletter and discover a world of audiobooks.