Get our Newsletter

-

- Reviews

- Narrators

-

Features

- Audiobook ClubStart a conversation with your book club

- Best Audiobooks2023 Best Audiobooks

- ArticlesDiscover the diverse voices of audiobooks

- NarratorsSpotlight on popular narrators

- AuthorsAuthors talking about their audiobooks

- Upcoming TitlesFind upcoming audiobook release announcements

- Kids and TeensListening selections for kids & teens with age levels

- Audie Awards 2024 Audie Awards

- Subscribe

- About

- Articles

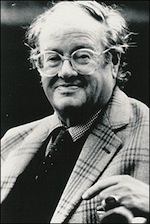

Talking with John Mortimer

Novelist/playwright John Mortimer’s writings share a preoccupation with lawyers (he himself is a barrister), a satiric edge softened by the gentleness of his wit and a whimsical melancholy underlying his humor. Moreover, he writes for the ear. He composed his first play, The Dock Brief, for radio; only later did it gain success with Michael Hordern on the West End and Broadway. Even his novels and memoirs seem designed to be read aloud. Perhaps that’s why he’s one of England’s most “audiobooked” living authors. Somewhere around 30 Rumpole of the Bailey titles alone are currently available. Mortimer’s favorite narrators of his own works are Leo McKern and Martin Jarvis. He, too, has stepped to the mic from time to time recording his memoirs. (Alas, Mortimer’s readings are available only in the U.K.) AudioFile was, therefore, pleased to ask Yuri Rasovsky, who produced the first American radio production of The Dock Brief, to phone him on our behalf.

AUDIOFILE: Your heroes, funny as they are, don’t seem to get on very well in life. Why is that?

JOHN MORTIMER: I think success is rather dull. I remember John Gielgud saying that in his career as an actor, his failures have been far more interesting than his successes. You can’t have a comedy about a successful person, can you? And you can’t have a tragedy about a successful person. All fiction, really, is the difference between people’s dreams and reality.

AF: A strain of sadness runs through your auto-biographical books, as well.

JM: I think pessimism is a very good basis for a cheerful life because you don’t expect too much, and good things all seem wildly marvelous.

AF: And the humor? Is that part of a cheerful life?

JM: Well, I think the best way to combat pomposity is to laugh at it, really. I noticed when I was defending cases in court that making the jury laugh made them more sympathetic than a savage attack. But also I try in my books to undermine the establishment from within by mocking it. That’s what Rumpole does.

AF: You seem to write for the ear. Is that on purpose?

JM: I do hope so. I mean it all comes back to my father going blind so that reading aloud was a big part of my growing up. And, of course, quite a lot of my work is dramatic, so the words must sound good because people speak them.

AF: Were you read to as a child?

JM: I was read to and also read aloud a lot to my father when he couldn’t see.

AF: So it seems fitting that a lot of your writing turns up on audiobooks. Do you enjoy audiobooks as a consumer?

JM: Indeed.

AF: What sort of things do you like to listen to?

JM: Homer. THE ILLIAD AND THE ODYESSY, I’ve had those read to me on audio-books. Long poems, poetry certainly. Long novels. I listen to Victorian novels, Dickens and George Eliot.

AF: Do you have favorite narrators?

JM: I’m not too keen on actors doing all sorts of different voices, the sort of squeaky impersonation of women and so forth. I like someone who sounds like a friend reading aloud to me.

AF: When you narrate your own work for cassette, do you strive for that kind of intimacy?

JM: Well, I do wish to sound friendly.

AF: For a listener new to your writing, what tape do you think they should start out with?

JM: My first memoir, CLINGING TO THE WRECKAGE, I’m quite proud of. I think it’s a good introduction to me.

AF: I enjoyed it.

JM: Nice of you to say so.

AF: Not really. Merely sucking up.

JM: (chuckles) Well, you suck up quite nicely.

MAR/APR 98

Photo © Julian Calder

The latest audiobook reviews, right in your inbox.

Get our FREE Newsletter and discover a world of audiobooks.